After Archimage Streams

Jake Davidson

“Think of what you experience on suddenly perceiving a shooting star: in this extremely rapid motion there is natural and instinctive separation between the space traversed, which appears to you under the form of a line of fire, and the absolutely indivisible sensation of motion or mobility. A rapid gesture, made with one’s eyes shut, will assume for consciousness the form of a purely qualitative sensation as long as there is no thought of the space traversed.” [1]

In our contemporary reception of information, the act of scrolling has become the de facto method of looking at text and image. The number of times we unlock our phones is an average of 221 a day, according to one U.K. study. [2] The act of touching an image in order to scroll is not exactly accurate. The capacitive mediation by which scrolling occurs requires an electromagnetically charged field that registers voltage drops when a finger presses any area of a screen. The body links with the screen as the device registers the finger’s interruption–a bond that did not previously occur in plastic joysticks, which register input through resistance. For at least the past two decades, the physiological chemistry of screen bonding has allowed devices to shrink while still being manageable by our opposable thumbs. In this text, I am thinking through the role of images as they are streaming live sights and augmented realities through pixel planes edging on the imperceptible. After this gradient of perceptibility, how will we register images that are unannounced, discretely bordered, and leave behind previous lexicons of familiar display?

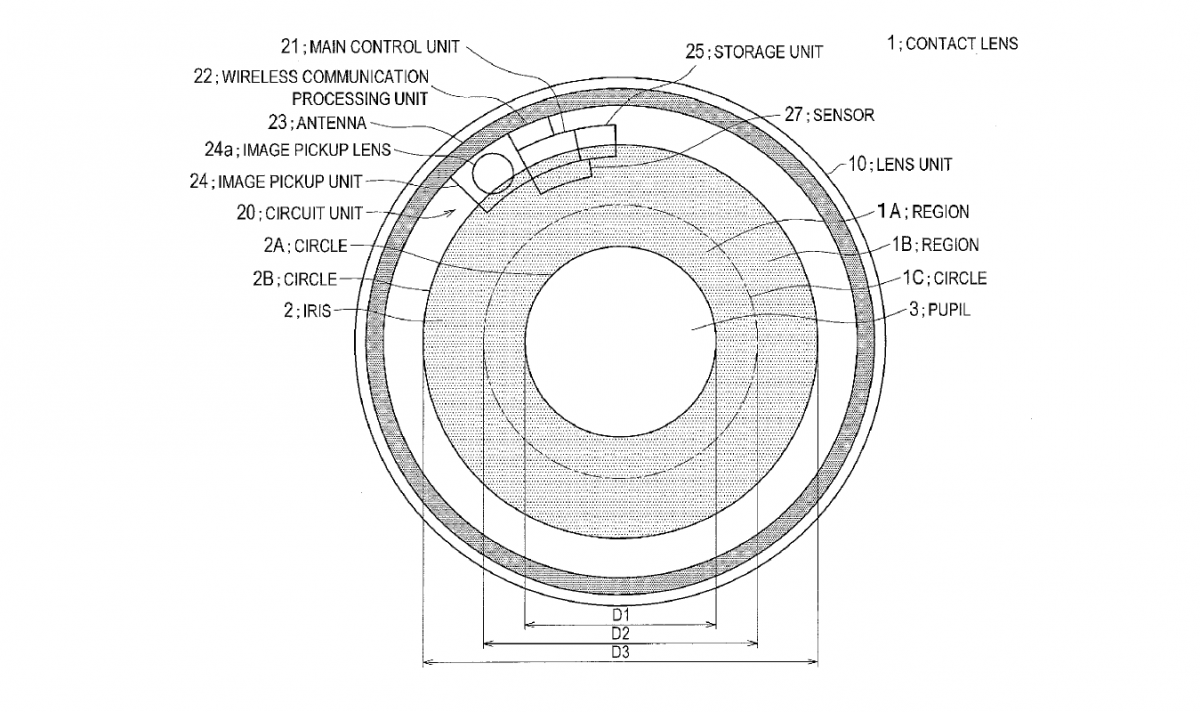

Until the 1940s, cinema projected images between 6-60 meters in front of an audience. Early films such as The Great Train Robbery (1903) sunk the divide between the literate elite and the working class (some of whom built the very train tracks shot in the film). With the advent of television, images were comfortably domesticated between 2-4 meters away from our eyes. By the 1980s, microarchitecture shrank tools capable of displaying images in the palm of our hands. Today, we hold screens roughly 15-25 cm away from us. This migration is midstream; display platforms in several universities are now being engineered to become a layer atop our corneas so that the distance between an image and our optic nerves is negligible (e.g. bioscribed images [3] ). The familiar convention of our psyches projecting onto images that appear outside ourselves is facing a shift, whereby images will soon be displayed from inside our bodies. The levels of intimacy with which we have come to know our bodies will soon be equivalent to the levels of intimacy with which we will know screen images.

Platforms for images, be they social media or other web-based publications, could themselves be thought of as positively and negatively charged ions linking us to sensations that, as histories of photography remind us, were always substantiated by our subconscious investments. Sensational frames around images, both on and off screen, can sequester the reach of information, impounding considerations for how an image might affect us. The Gorillaglass™ rectangle becomes a chameleon skin that surfaces a tendency for immediate sensations and emotions. Our grip on what images are not is loosened by the breadth of how images can impulsively make us react.

The flatness of images, alongside the recurring inability to animate screen images to the point of life-likeness [4], has created archetypical image experiences, or archimage streams. Despite miniaturization, wider contrast ratios/color gamut, and higher resolution, screen images have flat-lined in a zone of predominantly hasty challenges, or of affirmations, instead of the textural, spatial dimensions of virtualized realities that frequently escape the visible frame. Images that fester in the scrolling feeds of Facebook and Instagram seem to quicken the heart while indefinitely dictating non-screen experiences.

Conventional screen dimensions (standards that allow for cross-platform use) shrink relations with screens to such a degree that any change in screen size becomes a consumer holiday. First used in the 1940’s as a criteria by the National Television System Committee (NTSC) in North America and later developed as part of the 1950s Phase Alternating Line (PAL) in most other countries, these broadcasts required uniformity in order to accurately transmit audiovisual content. This was limited initially to 480 interlaced lines on an image screen. TV broadcasting was eventually co-delivered by other content means on cable wires, offering more bandwidth performance and greater system reliability. Alongside image broadcasting was the rise of the World Wide Web and internet connectivity in the 1980s. A computer, unlike a television, does not require interlaced broadcast standards. Resolution can be modified based on dozens of factors such as chipsets, display proportions, and screen sizes. While on the one hand many of these changes liberated the scale and clarity of images–HD and now 4K resolutions as a current direction, a fundamental barrier to resolution lies in the fact that screen images are still being produced by proportionate square pixels. The current limitations of screen image technology demand that we exclusively see and interact not with content projected into the world but as data exclusively tunneled alongside it.

As screen images are almost entirely accessed through stratospheres of pixelated indeterminacies, corporate custodians of images–Adobe, Getty Images, Google and their acquisitions–have made giant searchable archives and immediate access points the norm. These archives have become innumerable; a waxy surface building above collections that are algorithmically efficient to the point of convincing many users not to look elsewhere. One may see this condition as taking a hike up one mountain (say, Denali in Alaska) as equivalent to hikes up other mountains. Above the wintery swamp, through the hills and over the clouds, rests a mountain with a very sharp peak covered with images of snow. As spring arrives, melted ice sends a stream down the mountain where it divides into estuaries that lead to an ocean of deep, blue respite. Even microarchitecture must heed the edicts of physics.

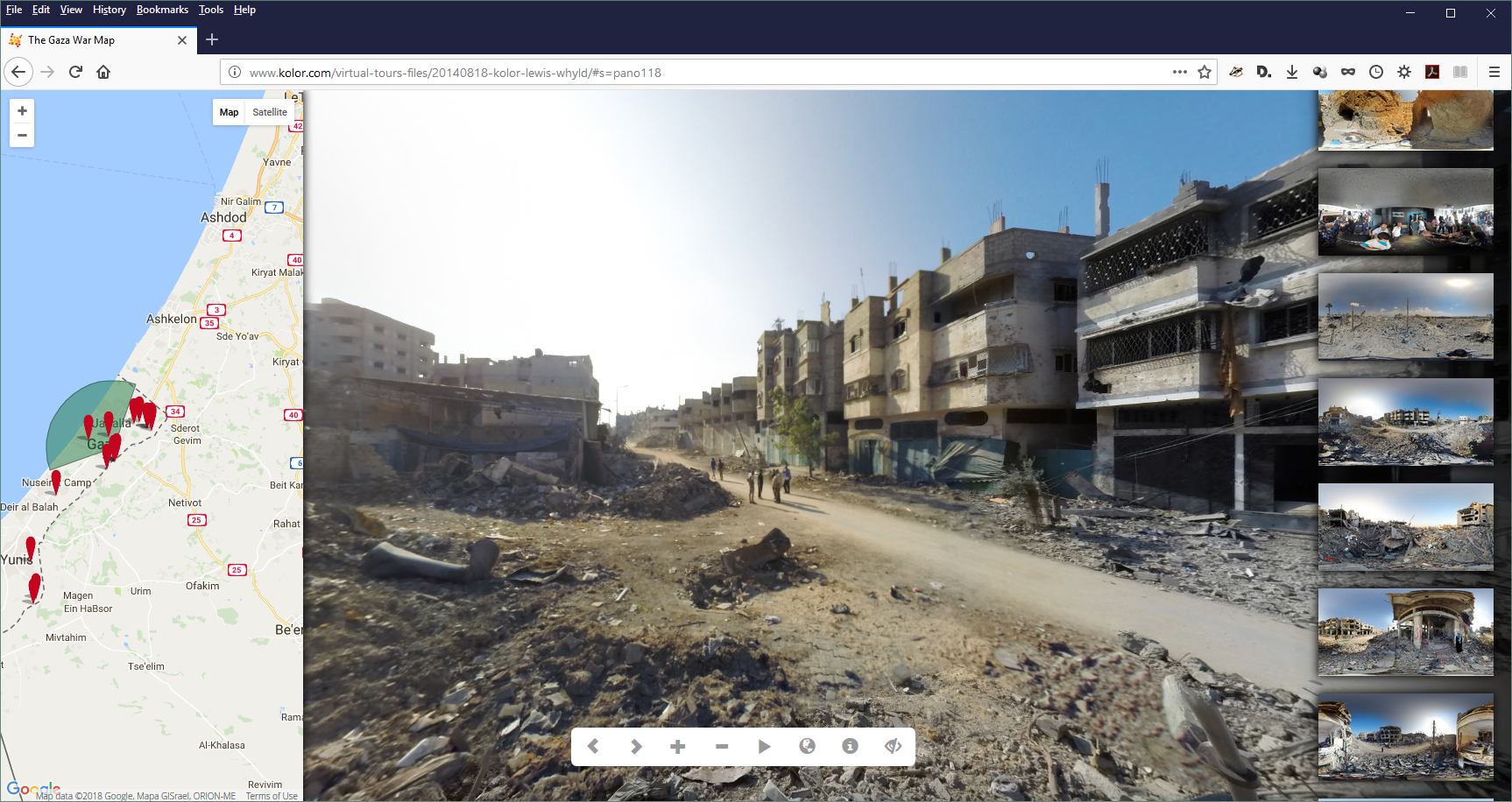

Understandably, there are limitations that prevent a smooth, three-dimensional image on demand. There is no assurance regarding what sensations, or lack thereof, this will bring. Nevertheless, retaining flat, rectangular configurations perhaps encourages the world to retreat from a once-globe shape back to a flattened fantasy. Nationalist governments seize opportunities that rely on such modalities of sensation-making. For example, the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is keen on this, as was revealed during the summer of 2014. Under Israeli command, the Gaza strip was once again plummeted with such a large quantity of explosives (many of which are banned internationally [5]) that bodies of family members were unidentifiable. During the siege, Netanyahu called murdered Palestinians the “telegenically dead.” [6]He argued that Hamas had broadcast images of bodies scorched by the shelling in order to garner international sympathy. His position was rooted in the claim that images of evidenced murder overstate harm. It appears as though the expanse of telegenic death (in images) can make nude the autocrat; and yet the very same images can just as quickly embolden a megalomaniac’s powerbase. During the same summer, a few compelling screen image projects emerged that explore this ambiguity. For example, the Gaza War Map [7]is a series of 360 degree images that one can navigate and magnify, or simply watch as the camera pans over totally shelled neighborhoods. Google’s open source mapping platform offers geotagged locations—important given the unfamiliarity with and inaccessibility to Gaza.

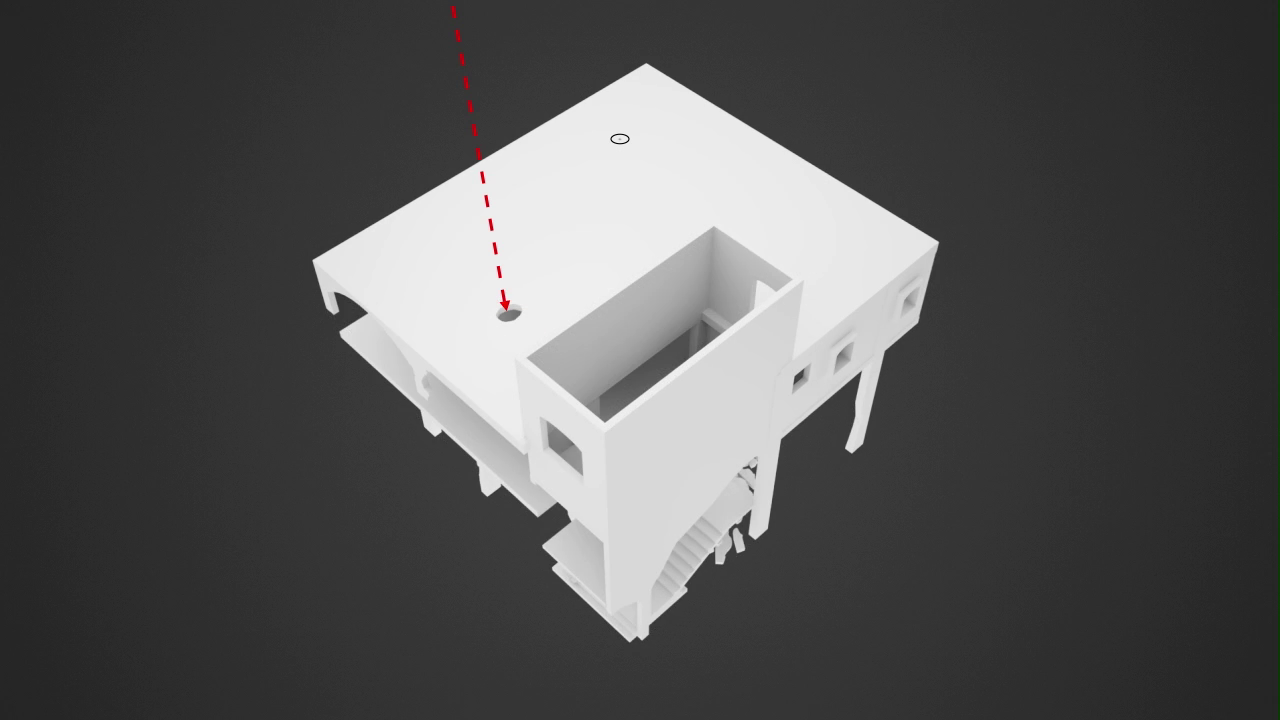

Another project run by Forensic Architecture Laboratory [8]uses image, sound, and metadata analysis to provide court-approved evidence on specific cases. During the 2014 Gaza incursion, research using drone footage, 3D terrain renderings, and legal documents revealed the Israeli military practice Roof Knocking. This practice converts innocent Palestinian citizens into voluntary human shields who are no longer protected under law if they do not evacuate their homes following the sound of a small metal ball dropping on their roof, which signals a warning that the house will be bombed. The contributions that screen images can make towards reconnaissance–images sculpting a trifecta of perpetrator, savior, and narrator–invite more thorough capturing. Image information can interfere with accountability in ways that can make organizing difficult. From this, the distance of violence can grow further away as screen images of violence come closer. Whichever terms may be used to mark this image shift, it is important for artists to think deeper about the various shapes of virtual presence instead of treating them as exterior equipment. Eventually, failing to register the psychodimensions of fabricated worlds inside of us might result in further compromising our capacities to recall. Dystopian ideas usually amp up the dramatic effects of beta technologies, while traditionalists mock any long-term contributions image-immersion may have. Neither are really suitable for confronting the cliff of cognitive-industrial image production that stands before us. There seems to be an emergent need to make fantasy a utility; to involve more of everyone to assist in imagining images replacing experiences. With this comes a tremendous capacity for large social groupings to be influenced and thus makes emerging virtual technologies a possible perfect storm for creating conditions inside one's sensory matrix, where the capacity to recall is rendered obsolete. In other words, preformatted registers of the world around us.

This leads to another thought: in 2016, there was a much-circulated photograph of the murdered Russian ambassador Andrei Karlov laying on the floor of a contemporary art gallery in Ankara. His life was taken by a young, off-duty Turkish policeman who was posing as a member of the ambassador’s security team. The assailant made his intentions clear: it was an action carried out to stop the massacres in Syria. The image that bolted across news sites and won photograph of the year, unintentionally crystallized a depth of field slip. A microphone is seen directly facing a framed photograph, as if it were mocking the reliance on images dictating worlds too violent to be seen.

- Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1928)

- Digital Strategy Consulting, study conducted by Tecmark, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.digitalstrategyconsulting.com/intelligence/2014/10/average_smartphone_user_checks_device_221_times_a_day.php

- Ghent University, STRECHLENS – Deformable platform with thin-film based circuits and ultra-thin Si chips for smart contact lens application https://www.ugent.be/en/research/research-ugent/trackrecord/trackrecord-h2020/msca-h2020/msca-strechlens.htm

- “Harun Farocki spoke of how digital animation hit a limit (not unlike the “winter of artificial intelligence”) when it tried to reconstruct the human walk” A Critique of Animation, Anselm Franke, e-flux Journal #59, November 2014

http://www.e-flux.com/journal/59/61098/a-critique-of-animation/ - Israel Use Banned Weapons, Al Monitor 2014

http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/08/israel-use-banned-weapons-dime-gaza-war.html - Netanyahu’s Telegenically Dead Comment, The Intercept, 2014

https://theintercept.com/2014/07/21/netanyahus-telegenically-dead-comment-original/ - Gaza War Map Project. 2014

http://www.kolor.com/virtual-tours-files/20140818-kolor-lewis-whyld/#s=pano115 - Case Study no. 4: Beit Lahiya, Gaza, January 9, 2009, Forensic Architecture

http://www.forensic-architecture.org/case/drone-strikes/