The Words Were Limited

Ala Younis with Nora Akawi

August 30th, 2020

Nora Akawi: Your work on Baghdad is not a static project. Rather, as your research evolves, new versions of it are exhibited, presented, and published. Among the versions of the work that I saw was your presentation of Plan (fem.) for Greater Baghdad at e-flux in New York in April 2018. I was struck by your elaboration on one of the project’s recurring titles, The Works Were Limited. One of the characters involved in Baghdad’s modern architectural history and a key protagonist in your project, Iraqi architect Wijdan Maher (1945-2020), was recalling why many Iraqi women in the field of architecture couldn’t set up their own practice. As recent graduates, they had to pursue junior positions in offices usually run by the sons of established men, because the latter had started their careers earlier and thus secured clients and projects. You mentioned that this was an important juncture in your work because perspectives like Wijdan’s added a new dimension to the period (from 1956 onward) you were researching, one commonly perceived as prosperous and abundant in construction projects. Wijdan, however, was speaking of professional restrictions based on gender. Her words, “the works were limited” solidified a key contradiction between two overlaying narratives of development in Baghdad in 1970s and 1980s: one of abundance, and one of restriction.

This can be considered a defining moment in the trajectory of your research, which was previously based on written and official accounts of Baghdad’s modern architectural history, which excludes many perspectives, particularly those of women. The words, too, were limited. In your work, however, this restriction quickly becomes a narrative opening. This is when your research and historical narration begin to rely on materials outside of the written word and outside of official historical archives, and begin to construct a different language, an alternative archive.

Your artistic practice here is at once a commentary on, and an intervention in, the writing of architectural history. Unsatisfied with restrictions imposed by official accounts, you bring in new, previously marginal materials and formats that you deem central to the act of "rewriting ourselves into the world," as the editors of Makhzin put it. Can we start this conversation by laying out the components of this other language, and reflecting on how they interacted with the written archives that your work, in its previous iterations, was based on?

Ala Younis: Wijdan Maher said that she had the language but not the interest (or perhaps the drive) to write the history she was part of. She recalled how others had found a way for their narratives to be printed even if they had not mastered the language their books came out in. Perhaps her hesitation did not come from a place of restriction per se as much as from the kinds of political histories she or fellow (female) architects would end up writing or becoming implicated in. For example, the development projects of the 1970s and 1980s in Iraq, a time when female architects were graduating and becoming active, were projects administered or tendered by the Baathists. The circumstances that led to and followed the fall of the Baath regime in Iraq have made claiming any professional relationship to the regime’s governmental projects quite problematic. Such information can overshadow other ideas, projects, or achievements these architects could have had in their life and practice. By remaining silent, or ambiguous about the period, these architects are setting priorities. Unfolding the extended history of a monument (like the Martyr’s Monument [1983] for instance, a special structure that was designed before the Iraq-Iran war, but later dedicated to it) could save the monument from being demolished at a time of reconciliation between the governments of Iraq and Iran. Perhaps we could refer to silence, the decision to defer the moment of writing our history to later times, and limited access to information as components of this other language.

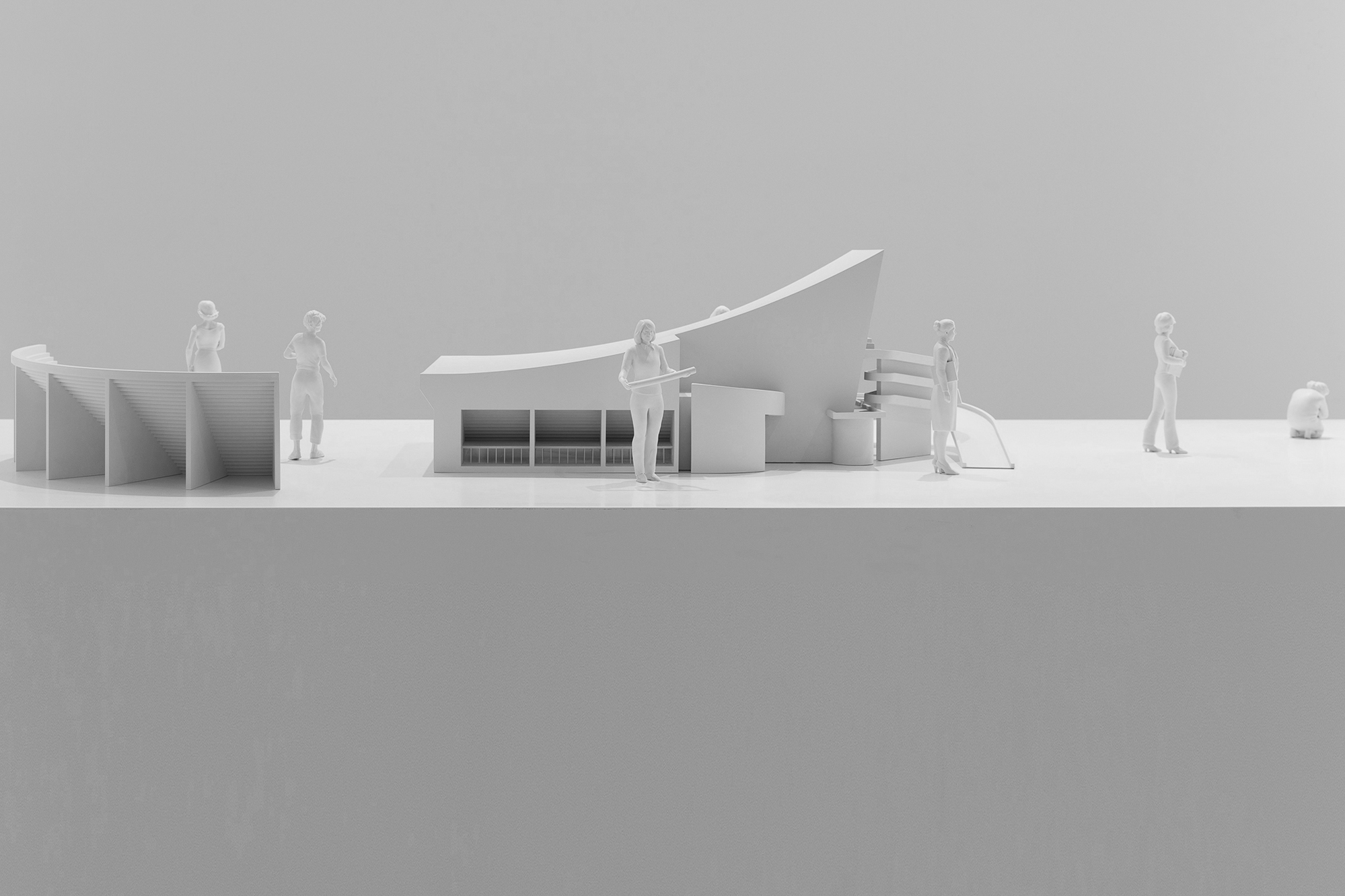

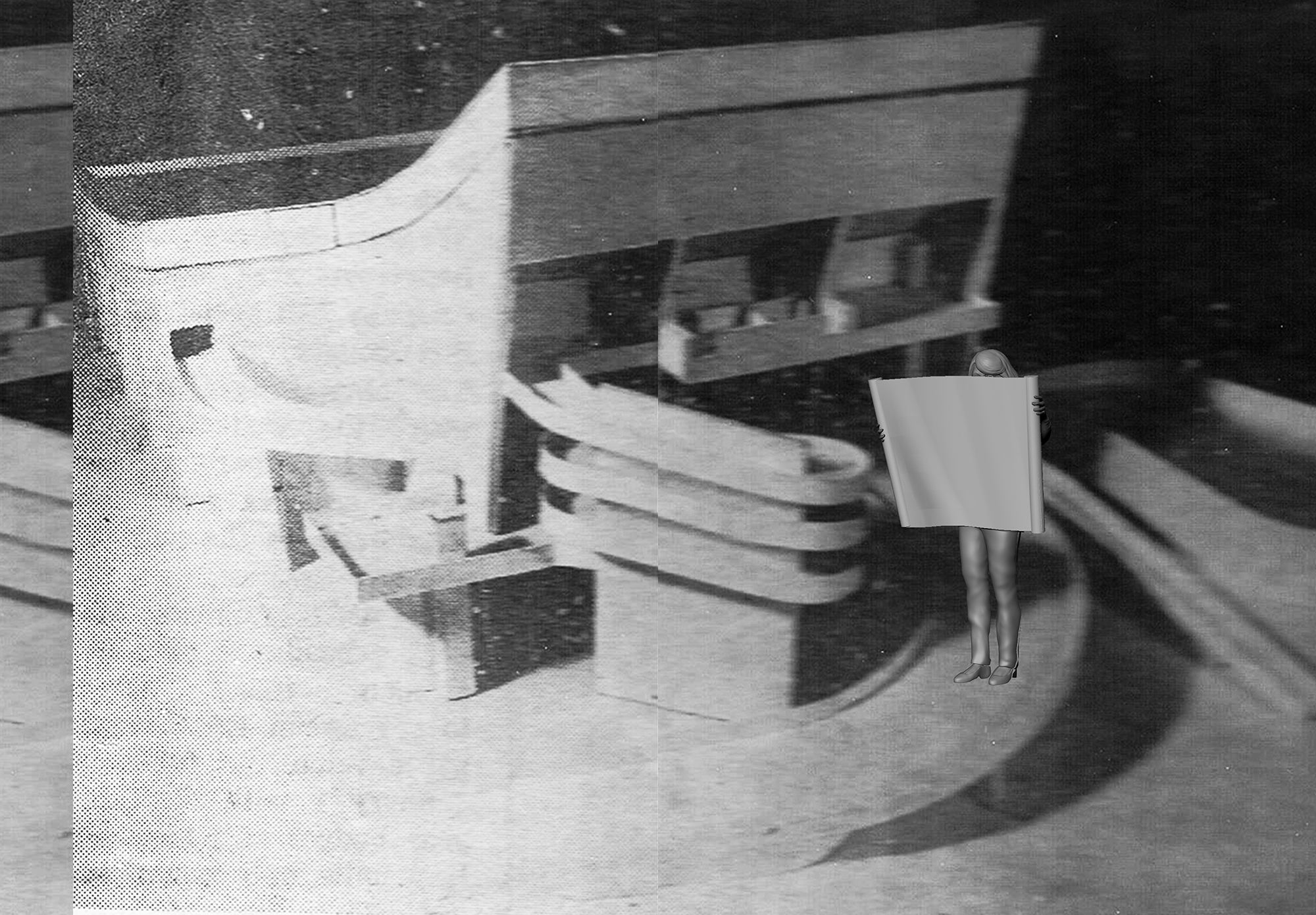

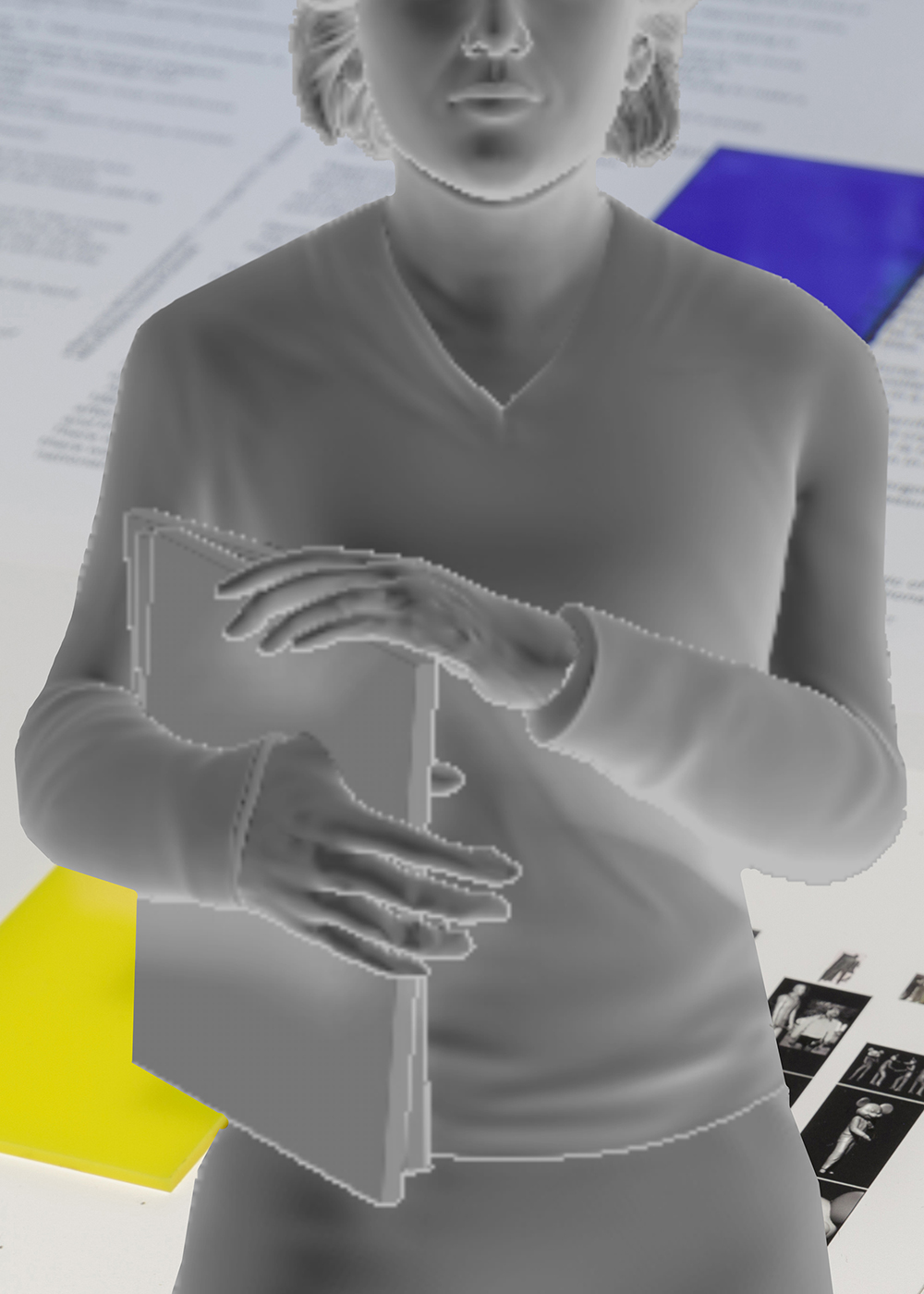

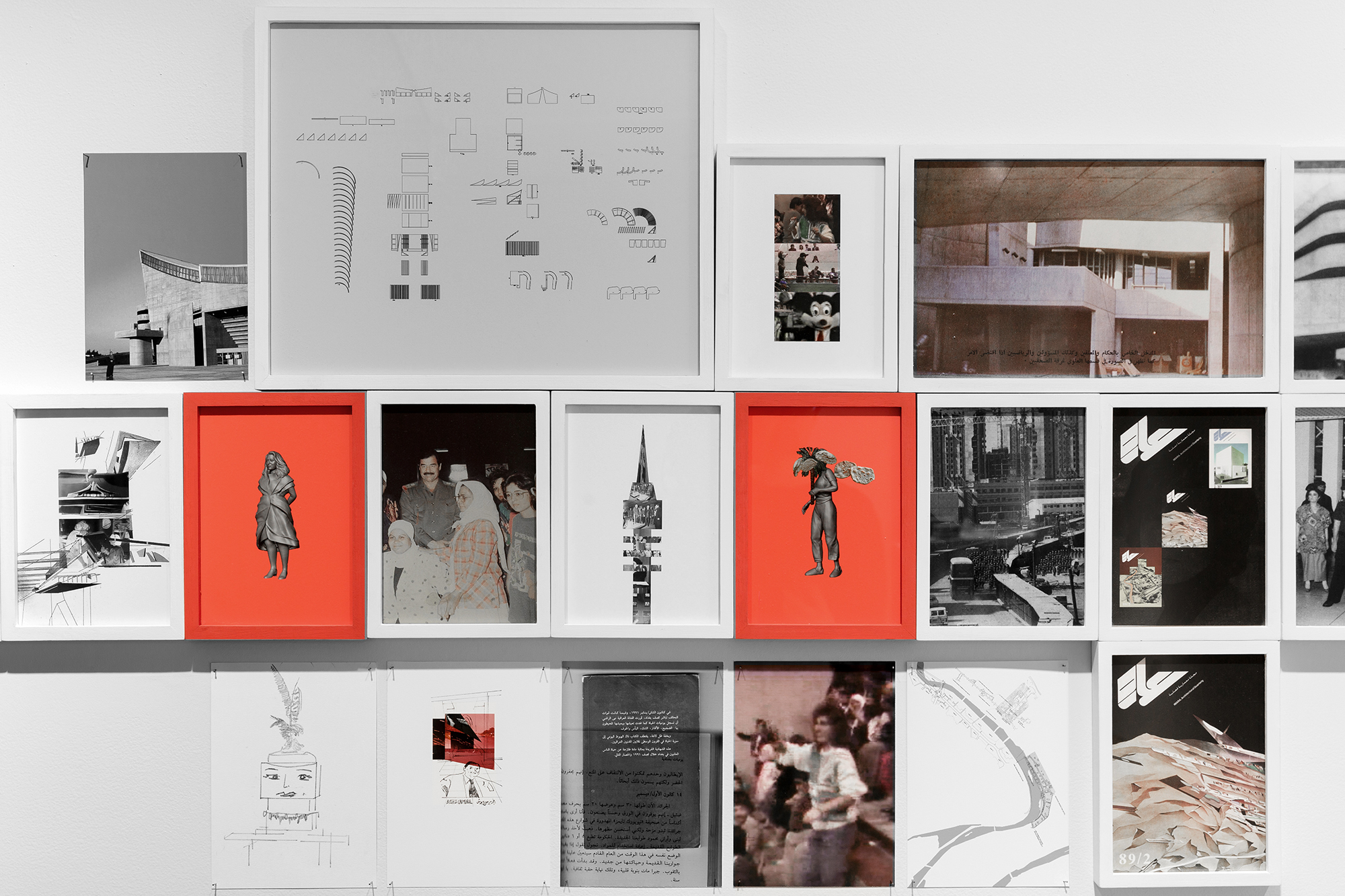

Plan for Greater Baghdad started when I came across a set of 35mm slides taken by architect Rifat Chadirji (1926-2020) in 1982 of a gymnasium in Baghdad. The gymnasium was designed by Le Corbusier (1887-1965) and metamorphosed through numerous iterations of plans over twenty-five years before it was inaugurated in 1980, and named after Saddam Hussein. After 2003, when Saddam, his name and images were removed from everything, the gymnasium was renamed as Baghdad Gymnasium. As I collected these iterations of plans from dispersed narratives, my project examined how monuments in Baghdad were ideologically inscribed and their survival linked to power. The dispersion also pointed towards missing images that were pieced together from fragments of existing images and from records of gestures retrieved from representations and narratives by local artists, such as those appearing in the story of Jewad Selim’s making of Liberty Monument (1961). The second iteration of the work, Plan (fem.) for Greater Baghdad looked into the blind spots within these retrieved narratives, into what remains unidentified in the spaces of dispersion. It traces the content or characteristics of a history of architecture from fragments of female influence (not necessarily all architects) in architectural practices.

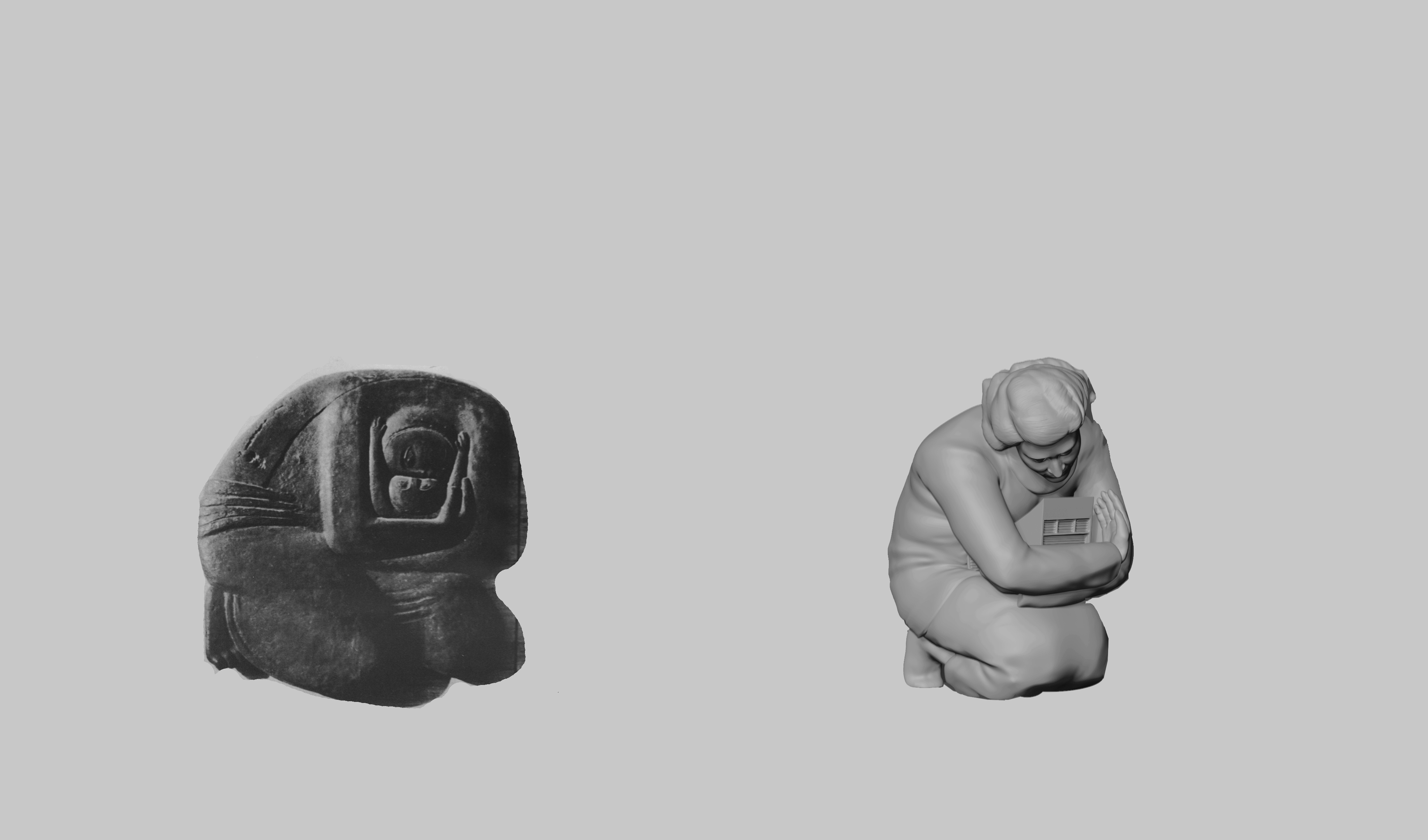

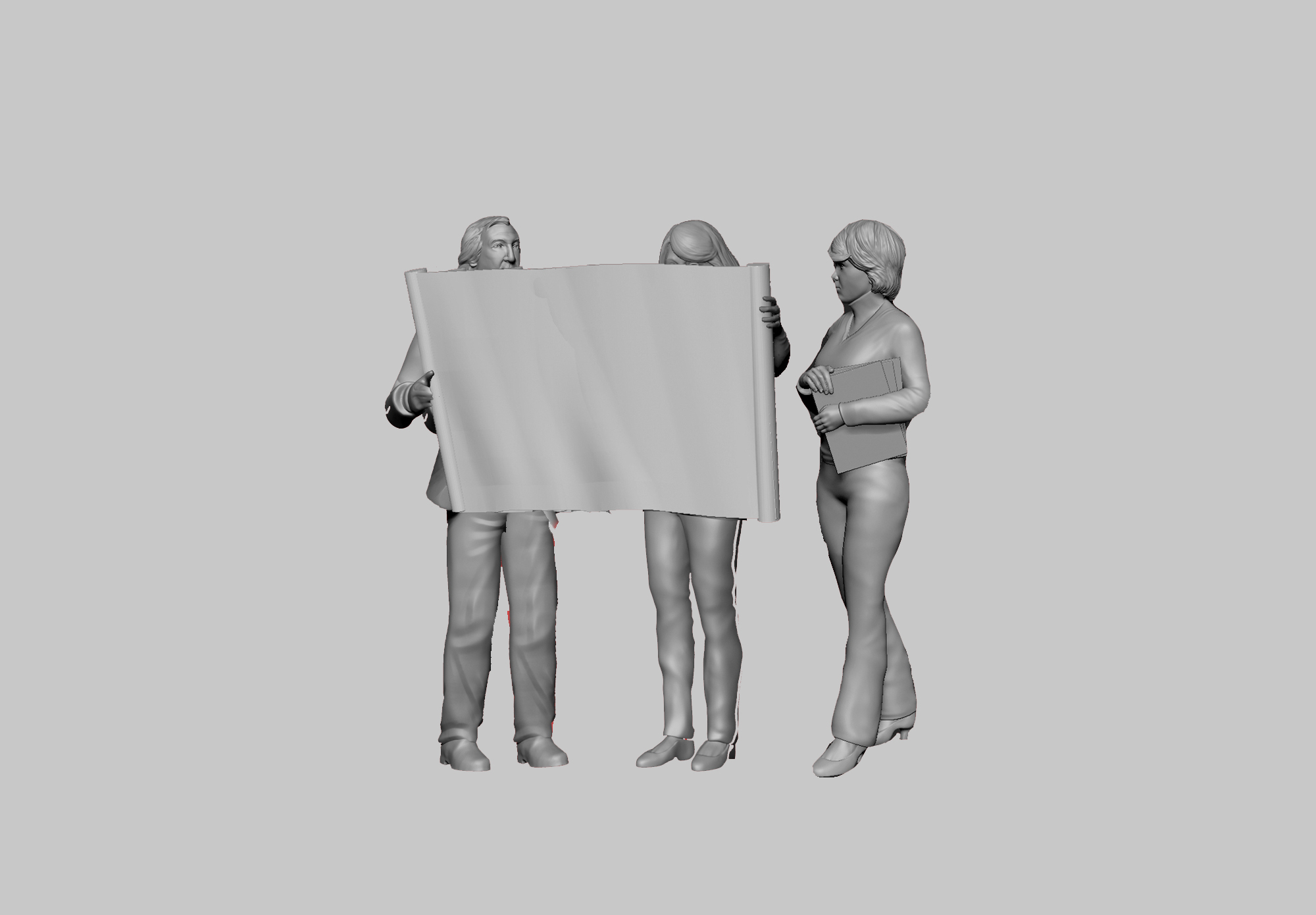

For one of the sculptures, I borrowed a position from the Liberty Monument: a woman cradling a child. Here, she is cradling the model of the Baghdad Gymnasium, referencing an architect employed at the Ministry of Housing and Public Works, who, in 1973, pulled out from the ministry’s drawers Le Corbusier’s completed but abandoned drawings of the gymnasium. His drawings had been forgotten after he passed away in 1965, when new political regimes were about to take over Iraq, subsequently changing the country’s master-plans and architectural commissions. Le Corbusier’s contractors were to finalize the drawings and preparations for the project, while Iraq Consult (Rifat Chadirji’s consulting company) was appointed the local consultant for it. Architect Nada Zebouni and her colleague were in their final year of architectural studies in 1974 when they interned at Iraq Consult in Baghdad. They later interned at Le Corbusier’s contractors’ office in Paris, where they worked on the drawings and the modelling of the gymnasium. Nada brought back a picture of the model, the first 3D realization of the morphing project’s final form, and the Iraq Times published that image along with a news article on the project’s developments. I found these stories from interviews or hints within the published accounts of architects who worked at Iraq Consult. Nada pulled out the scans of the Iraq Times article from the few materials she carried with her to Canada. Nada also sent scans of the covers of the three issues of Imara, Wijdan Maher’s specialized quarterly on architecture published in 1989. In another publication I found a published photo of the dean of architecture department at the University of Baghdad with two of her female architecture colleagues, taken on the ramps of the gymnasium when they were students in 1982. These alternative archives or collections of studentship were another fascinating site of investigation and inspiration for me.

From other documents in the Le Corbusier Foundation archive, we understand that the construction of the gymnasium was awarded to a Japanese contracting company, and work began when Rifat Chadirji was in Abu Ghraib prison (1978), and finished shortly before he was released (1980). This period was another constructive one, as Balkis Sharara, Rifat Chadirji’s wife, carried materials and manuscripts related to her husband’s work in and out of the prison for him between 1979 and 1980. This not only changed the quality of his time in prison, but also provided us with one of the prominent books on architectural practice in Iraq, Al-Ukhaidir and the Crystal Palace. She was assisted by Wijdan Maher, who worked in the afternoon as a senior architect in Iraq Consult, after her day job at Iraq’s tourism board. Wijdan was also part of another consulting team that supervised the construction of the Martyr’s Monument in Baghdad. In a phone interview from her home in London, she mentioned her magazine, Imara, in passing. She could not provide images of it, and when I asked for her photo (to do my digital sculpture of her), she said that an image of her was published in that magazine. She related any identification of her face/work to finding of the magazine. It was like a loop of puzzles.

Wijdan founded Imara in 1989, as an architectural quarterly. She dedicated the second issue’s feature to Zaha Hadid’s award-winning project, The Peak. Wijdan made several assertions related to how she refused a government takeover of the publication; she wanted it to remain independent, and so editors, translators, and solicited contributors were all voluntary. She was printing her fourth issue when the Iraqi army’s invasion of Kuwait put an end to the magazine and to her stay and architectural practice in Iraq. Aside from the publishing effort and network of contributors, how much could the making of this magazine tell us about the vents Wijdan chose to identify a project of her own as a translation of her position in a dense and problematic era of Baghdad’s architectural history?

Coming back to studentship, I also found that after the invasion, two books on deconstructivism appeared in Baghdad, and architect and academic Maha Al Bustani got hold of them for a price that was double her salary. After she self-studied the architectural style with a focus on Zaha Hadid’s illustrations of architectural plans, she later taught them along with her husband to students of architecture. Since there were no examples of deconstructivist architecture in Baghdad, and Zaha Hadid’s architecture was not yet built anywhere in the world, the two scholars taught deconstruction through examples of poetry. This is how architecture was re-translated in words, when architectural examples (in Iraq) were limited.

This was when Baghdad was under American sanctions; any architectural work was related to renovation, while life and infrastructural services had deteriorated massively. Living conditions in the 1990s sanctions era were very different from those of the Iraq-Iran war in 1980s. Between 1980 and 1988, Baghdad and its busy construction work remained active, foreign architectural and contracting companies continued to work there despite shelling and limitations on travel, insurance, and hard currency. Wijdan recounts that there was also a big draft of Iraqi males, which led to a society where women drove buses and formed an overwhelming majority of the employees at the Ministry of Culture, among other stories. The Gulf War in 1991 started by striking Baghdad’s infrastructure; the government buildings (including ones designed by Rifat Chadirji) were destroyed, and services like electricity were cut off. Those who had learned from the Iraq-Iran war to stock meat had to throw their stocked meat to stray animals in 1991 because there was no electricity to operate the fridges and freezers in which it was kept. Medicine, spare parts, and even paper became less available. We learned these details from artist Nuha al Radi’s Baghdad Diaries. The subjects and events in this book are not about her art, but the details of surviving Baghdad and its government, when under sanctions. To leave Iraq, Nuha had to file an application claiming she was illiterate so that she pays a smaller fine. Lying and weakness are far from the acts of heroism or feelings of pride that prompt the writing of the other Iraqi autobiographies. It was about living in a dystopian version of the city after witnessing its busy development in the previous decades.

This is an experiment on historicity, on understanding the position in history from within the absence of “heroic” female architect figures, as a way to rethink heroism versus historicity, and what roles they had while this history was being written. After I met Wijdan in person in London, and listened to her response to my approach and choice of materials in Plan for Greater Baghdad, I was terrified that by possibly emphasizing gender and class asymmetries, I was further privileging one dimension of a controlled historical narrative. I felt that perhaps my work was falling within the structures of knowledge that it was attempting to challenge. The first presentation of my project is strongly tied together, but the second is not (in any apparent way). This un-tied presentation is a way to imagine a writing of this history that resists a normalized writing order, and remains largely oral, traceable through few written mentions, sometimes even deliberately obscured. I told Wijdan that I was willing to help write these missing parts, or if she was willing to write them herself, I could work from that. This is when she expressed her view on language and drive for writing.

NA: Let’s pause for another moment on Wijdan’s explanation about having had the language but not the interest, or drive, to write this history, while others had the intention but not the language, and so they had people assist them in writing their books. The interests, or intentions behind certain narrations of history often come through by paying attention to the materials this history relies on or produces. Your work allows us to explore the specificities of a feminist narration and its materials, both in general terms, and in relation to the architectural history of this period in Baghdad. You referred to oral accounts and testimonies, even to dreams, to fragments of images, to multiplied or disguised characters, to several attempts at three-dimensional models in portraying ungraspable features, to un-tied presentations… All of these elements come together as the opposite of a determined, authoritative version of history, but rather as an opening into its multiple alternatives and potentialities.

At the same time, in the Liberty Monument by Jewad Selim that you refer to, the women portrayed are crying for their martyrs or protecting the children. In your project, which is influenced by this monument, the characters (some of whom you mentioned above) are portrayed as guardians of the archive, of history, even as it excludes them. They facilitate the writing of others’ books without authorship, as did Balkis Sharara, or they safeguard key archival materials of Baghdad’s architectural history without credit, as did Nada Zebouni. Perhaps we can consider your own work and research, through extensive readings and conversations, also as part of this long-lasting practice of guardianship.

What’s particular about your work here is in the focusing on the blind spots of the modern architectural history of Baghdad as we know it, while also acknowledging the inevitable cracks and fissures in the research process. You spoke of dissociated archives, silences, multiple time zones, and issues of trust when speaking of the times under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, or of potentially unwanted associations by certain architects with some of the architectural histories of the time. You also spoke of the choices to not write a history in order to protect architecture from the destruction that could result from such association.

We’re faced with a multiplicity of approaches to the archive, which together are choreographed as a mode of protection while facing potential loss or destruction: they include writing and indexing, multiplying and reproducing, smuggling and safeguarding, and even deliberately obscuring, all at once. Your archival practice in this project operates through a variety of such approaches, yet they seem to steer away from categorization and indexing, and towards reformulations, reconfigurations, and the propositions of alternative fictions. An interesting contrast is Rifat Chadirji’s photographic archive, from which Mark Wasiuta and Akram Zaatari developed the book Rifat Chadirji: Building Index (2018). Chardiri’s archive is repetitive, systematic, categorical. In Wasiuta’s words, “this collection reveals the twists and folds of archival authority, and legibility.” In the context of a conversation shaped by questions on language, I wonder if we can dwell on the links between authority and legibility, and what this says about the legibility of a feminist version of history, one that refuses a systematic archival authority. Going back to Wijdan’s comment, perhaps it’s precisely the disinterest in unshakable legibility, and the lack of dictated and determined meaning, that qualifies this history as non-authoritative, as feminist.

AY: I can’t be sure if I discovered the Baghdad Gymnasium in 2010 from the photos taken by Rifat Chadirji and posted on Archnet.org first, or from a Wikipedia page that made me look for the photos. Afterwards, I visited the archives of the Le Corbusier Foundation in Paris and looked into the materials they had there. I also visited Rifat Chadirji at his home in Beirut, after, upon his request, finding and reading all his books. In fact, I read them all except one, A Wall Between Two Darknesses, which he co-authored with Balkis, but I will return to this book later. Over the course of four years, I was researching a dual-layered timeline that puts developments in the gymnasium’s story against other events in Baghdad that could explain to us parallel histories similar or different to that of the gymnasium. For instance, what other monuments and buildings came up and down in the city at the time, what changed as government institutions introduced new administrations or mandates, who was appointed, lost her job, passed away, got imprisoned, flew in or out, and when local currency fluctuated, and so on. All these were parallel histories that explained to us the delays or developments in the construction of the gymnasium. As I said, I made these timelines using materials found in archives, written books or documents, and through the stories of the main protagonists. The power relations that dominated the materials and narratives presented in the Plan for Greater Baghdad(2015) left women, in my view, out of this presentation (premiered in 2015). At the time, I did not want to give a nominal or courtesy mention of their work, nor had I located materials that could present narratives of junior architects, students, and housewives as being as glamorous as those of the starchitects and presidents presented in my research.

Rifat Chadirji thanks Balkis Sharara in the first page of Al Ukhaider and the Crystal Palace (1991), but explains how he wrote this book in prison in their joint book A Wall Between Two Darknesses (2003). The latter is made of alternating chapters on the couple’s experience of prison, her from outside its walls and him from inside. As I realized this composition process, I reread all the materials I had accumulated for the first edition of the project, and started to specifically note not only how female efforts were mentioned, but also the gaps, absences, and incomplete stories in these mentions. This revisitation ran in parallel with this other round of interviews and inquiries, with Nada and Wijdan among others, and targeted the senior and junior architects who worked at Iraq Consult, and in particular on the Baghdad Gymnasium project. I was no longer fixated on the story of the gymnasium, but used it as a guide into tracing and locating female interventions and presence within the history that surrounds it. For instance, I looked for every mention of the gymnasium in the architecture books made in Baghdad and that focus on it, and found mentions in two of architect Shereen Ihsan Sherzad’s textbooks, Principles of Art and Architecture (1983) and Glimpses of History of Architecture (1986). This was an interesting find because Shereen was the daughter of Rifat Chadirji’s partner in Iraq Consult, so she was very close to the consulting office that supervised the construction of the gymnasium. I was becoming part of this history, too, as I recognized her name from my architecture thesis jury back in 1997 at the University of Jordan. Her brother also taught us in the final year in my studies. I had wondered why we never heard about the gymnasium while studying architecture (between 1992 and 1997).

Finding two textbooks by an architect and an academic that I crossed paths with very early on was representative not only of the Baghdad Gymnasium’s history, but to gaps in my and other local architects and students’ relationships to it. The drawings of the unbuilt architecture of Zaha Hadid’s that Maha Al Bustani had to deal with, were the same reasons why I was, as a student, fascinated by an architecture that was so rebellious that it could only exist in drawings. Therefore, the lives and roles of students are essential in the feminist version of my project. In my mind, Nada’s photo of the gymnasium model and architect Saba Jabbar’s photo as a student on the ramps of the gymnasium from 1982 resonate with my holding on to images and drawings (but no models) from my own architectural studies until now. I do not speak of Rifat Chadirji who led these projects, but the architect who guest-lectured us at the University of Jordan in 1995. Zaha Hadid (1950-2016) is another figure that I personally encountered at a lecture at Darat al Funun in 1997. I sat among a large number of students and architects committed to learning more on her practice. The only memory I carry from this lecture, is her (seemingly) aggressive response to an unarticulated question that came from the audience. Interestingly, here, between the intention and the articulation of the question, “Do you use scale?” the words also seem to have been insufficient. The inquirer was probably referring to relations, and she probably understood it as a reference to a measuring device. Or perhaps it was the other way around!

Wijdan walked into the show Plan for Feminist Greater Baghdad at Delfina Foundation in London and said two contradictory things at two different times. At the show, she explained to her colleague that the work is not just about architecture, but when we met later, she critically said I was mixing architects with non-architects. I told her that this was intentional. I attempted to make visible the project’s own difficulties of representation, resorting to minor job detail, and re-constructing (or re-assigning) documents of those who could be instrumental, but not authors of the final product. For instance, as senior and junior architects cannot keep the drawings they work on in an architectural office, the archive of the office is attributed to its founders or principals, who in turn set priorities over materials to be deposited in other archives. This explains for instance why I couldn’t find much on other architects, including Wijdan and Le Corbusier, in Rifat Chadirji’s collection of his and Iraq Consult documents deposited at MIT.

I had only been able to locate one photo of Wijdan, I found it on Facebook but know it was taken from one of the magazines she had instructed me to look at. When I saw her in my show, I recognized her instantly. The exhibition tour was quick because she did not need any explanation of the history that was laid out on the wall. She brought to our meeting some of her photos at Iraq Consult office, and in the background, were images of buildings designed by Rifat Chadirji from her time as a senior architect at this office. There was a poster of one famous building that I showed versions of in the first iteration of my project. In the photos, she appears next to and in front of the poster. I couldn’t tell when these images were taken. Wijdan looked different in every photo. I had many thoughts on my mind: how architecture was the constant background in this office, how I was able to recognize her from just a single photograph taken decades ago, how much time I still have to take in the images she is now showing me. I was also worried: had I failed to accurately depict her features in the 3D model I made of her? Some aspects of her history were still vague to me.

Wijdan worked at Iraq Consult and the Tourism Board in the 1970s, was part of a consulting team that supervised the construction of the Martyr’s Monument between 1979 and 1983, and then a publisher around 1989. I asked what she did in between. “Several other projects,” she vaguely answered. I had developed a feeling that certain conversation topics were off limits. Her past was very political and too complicated to clearly articulate to a researcher in a first or second meeting. Therefore, any expressed interest on my end should remain professional and not political. If it is political, then I’d better not relate the question to Saddam Hussein’s character, time, or rule, and certainly not to her possible connections to it. If any part of that history is mentioned, I should express my intention not to use the interviewee or my work to comment on it positively or negatively. These architects do not want to dictate, or be instrumental in writing someone’s else version of history. Or perhaps, they do not want their words to be limited to politics; their process is a language inscribed in the monuments they participated in building.

We were exchanging stories on the Iraqi singer Kazem al-Saher, when Iman Mersal told me how, in 1993, she traveled to Baghdad with a group of Arab feminists in solidarity with Iraqi women suffering under American sanctions. Without prior notice or consent, the group was redirected to meet Saddam Hussein, who delivered a liberal, “feminist” speech. I identified with the way Iman described this speech; the style fit squarely with other elements that I had gathered in my research on the female history of Baghdad’s architecture and what might be related to it. For instance, Balkis’s sister, Hayat Sharara (1935–1997), researched the work of Nazik Al Malaika from the bits of content the poet’s family allowed Hayat to learn and later publish in her book on Nazik. In Hayat’s introduction to the published study Safahat min Hayat Nazik Al Malaika (Pages from the Life of Nazik Al Malaika, 1994), she writes that the research is incomplete and unrepresentative, acknowledging the research limitations and lack of information or non-disclosure requests she received from Nazik’s family. Iman’s description of Saddam’s words made me think of Hayat’s novel, Itha Alayyam Aghsaqat (When Days Dusked, 2002), in which, I assume, she described her life as an academic during the era of economic sanctions, assuming the character of a male university teacher. More dots were connected when I realized that the novel was published postmortem, by, again, her sister Balkis in 2002. In my installation, Balkis is presented as a carrier of these and her husband’s books, her sculpture is holding these books in her hand and under her arm.

I wanted to experiment with two vantage points of narrating the same history. Since Plan for Greater Baghdad was heavily based on materials from archives and written narratives, I wanted then to reproduce the whole timeline from a female perspective, and so Iman Mersal’s group photo with Saddam Hussein was essential. She did not want the image to roam the internet accumulating a wealth of fake stories on their encounter.

As you suggested, Nora, my research and presentations on Baghdad are not meant to be static, but rather prompt other versions of possibilities when exhibited. I do not intervene, fake, or fictionalize the elements or stories I present in this project; nevertheless, viewers should be able to tolerate multiple versions of stories when presented in creative or art projects. I feel sometimes protected by this space or possibility of fiction, especially when the narratives are not continuous or perhaps some facts are hidden or twisted by those who presented their side of the story. I do not exclude such narrative interventions, considering them alterations or evidence of personal or political fears. Another aspect of fiction is perhaps my attempts to create a visual document for stories that do not have images. To be able to construct one, I use references, merge accounts, borrow forms and gestures, and perhaps practice some authority on deciding how to name these documents and what they refer to or become part of. They become like limbs sticking out of ambiguities, cracks and inconsistencies in our situatedness within complex and intertwining histories.