Borderless and Brazen

Gülşen Aktaş with Aykan Safoğlu

September 25th, 2016

Translated from Turkish by Merve Ünsal

I'll be your mirror

Reflect what you are, in case you don't know

I'll be the wind, the rain and the sunset

The light on your door to show that you're home

The Velvet Underground & Nico, 1967

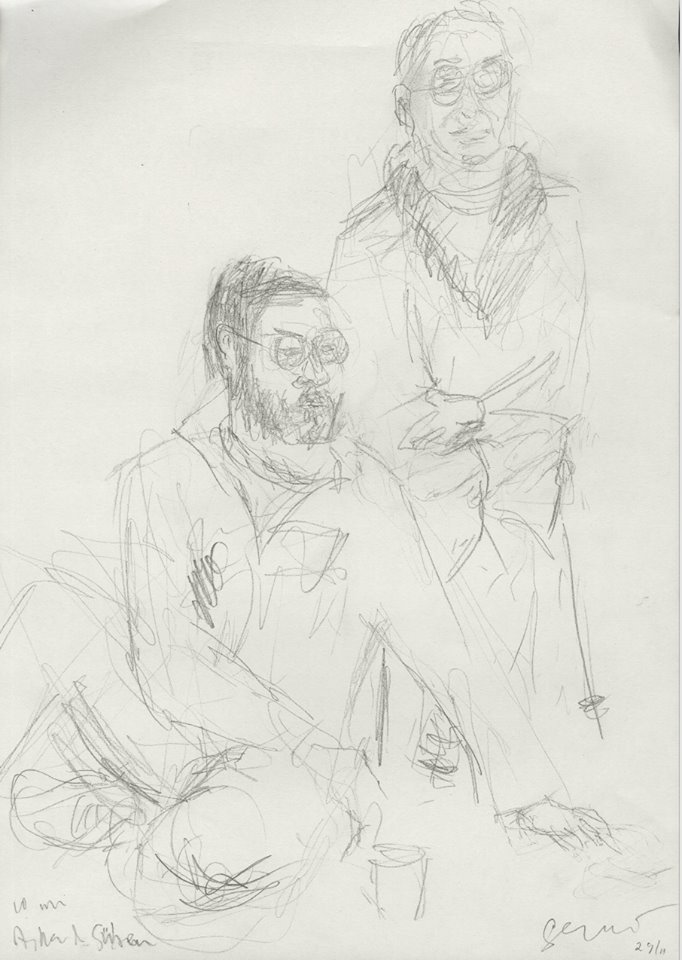

Gülşen and I met randomly at a film screening in Berlin of Beyond the Hill (Emin Alper) in 2012. During the Q&A, I asked Alper why he felt the need to use allegory to depict the war; there was a roar of applause in the room. Back then, I still ignored that the woman I saw when I turned around would become one of my closest comrade. The coffee we drank in the foyer marked the beginning of a friendship and life-long collaboration between a gay cis-man of White Turk identity born in the West of Turkey, and a Kurdish cis-woman born in Dersim, Kurdistan who dedicated her life to activism and women’s work in Germany. Berlin brought us together beyond our national and ethnic identities (Alevi Kurdish and White Turkish). Today, as I try to remember the path our friendship took, Turkey has intensified its war on the Kurdish people. Between November 8, 2015 and May 15, 2016, many Kurdish towns and PKK posts were destroyed by the Turkish military, leaving hundreds of Kurdish civilian dead. Activists, public intellectuals, academics and journalists who opposed this war and its regime were persecuted or incarcerated. As Gülşen and I got to know each other better, beyond different generations and socializations, the government’s supra-politics has gradually destroyed any possibility of democracy in Turkey. This is why Gülşen and I held on to each other and continue to do so. As I was thinking of a way to introduce the reader to Gülşen Aktaş, The Velvet Underground lyrics from the depths of my adolescence came spilling through my lips. This conversation is an occasion to share the feminist elements of Gülşen’s life that reflected onto my mirror and seeped into my art practice. We’d be happy if what emerged from of our friendship would eventually reflect back onto you.

*

Aykan Safoğlu : Since the beginning of our friendship, you’ve always talked about Dersim. Athough we scheduled our holidays there, we weren't able to go because of the military escalations last year. When you talk about Dersim, you always mention your elders. Especially your grandmother Xanperi and your grandfather Welo…Let’s talk about your childhood.

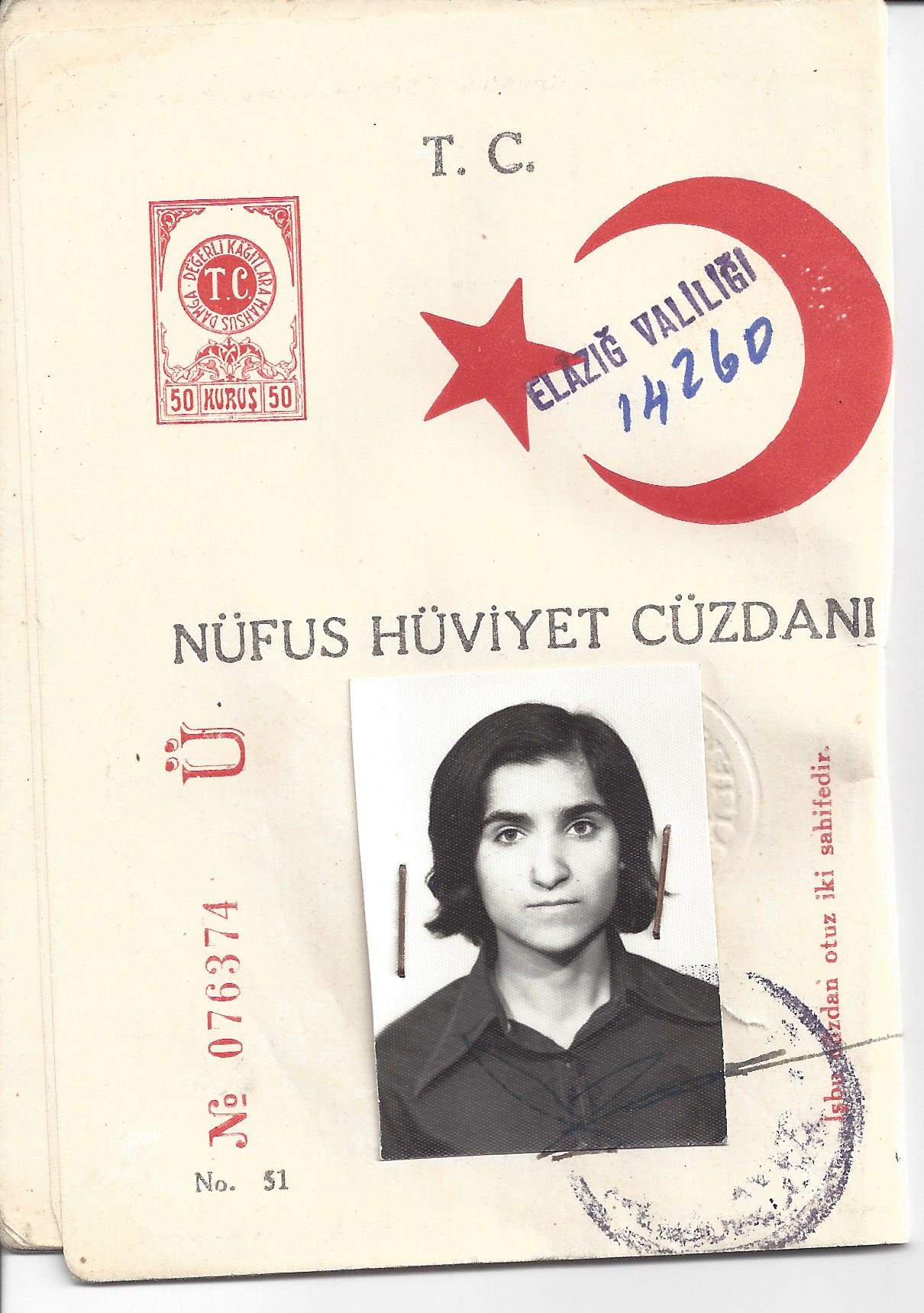

Gülşen Aktaş : I’ll never forget when we moved to Elazığ. We first moved from the village to Ovacık (a small town in Tunceli province within Dersim) on the back of donkeys, riding on sacks of bristles. Those bristles were really painful to ride on. I was jealous of those who walked.

AS: You have a twin sister and two other sisters, one older, one younger. We are talking about a family where women are more dominant. What did it feel like to grow up in such an environment? I’m curious about the decision-making processes in the family—how things worked.

GA: I lost my father when I was six. I remember the day of the funeral. When my father was a village teacher, the villagers got the gendarmerie to beat him up. So my paternal grandmother went to the mayor in Erzincan (a neighboring province to Dersim) and asked for my father to be transferred to Dersim. She was a bold, heroic woman. Although she didn’t speak much Turkish, she was able to go all the way up to speak to the mayor. They say that my grandfather was a coward—he always had tears in his eyes. My mother really loved my paternal grandmother; she’d always say that everybody should have a mother-in-law like hers. My father was an intellectual, but he wasn’t that strong.

AS: You chose your father’s vocation and became a teacher.

GA: Yes, I grew up in Elazığ and then went to boarding school in Ovacık. From there, I went to a boarding school for teachers in Urfa. Urfa, for me, was just a small village. I saw the opposite of what I experienced as an Alevi in Dersim. Urfa is a city full of bigots. I spent seven years there…

AS: In other words, this is the first story of migration you were able to process, with your twin sister. Do you remember moments of solidarity with fellow female students in Urfa?

GA: Of course the experience was a very positive one; we established very deep friendships. I was really upset that I hadn’t gotten my period yet; I wasn’t yet in puberty. The girls entering womanhood before me pressured me psychologically. Whenever somebody had a pimple and complained about it, I’d think that they were doing it on purpose. When you think about the image of a woman in society, you think about tits and ass. They’d call me “tuberculosis Gülşen”.

AS: So you were ostracized because you didn’t fit the heteronormative perception of womanhood?

GA: Yes, I was the ugly duckling.

AS: How was your relationship with your students as a young woman teacher in the village of Altınakar (rural parts of Diyarbakır)?

GA: Our school consisted of a male principal who was ten years older than me and another female teacher who was my peer. As the female teachers of the village, we’d go around to the villages nearby and register children who weren’t part of the school system, including Kurdish children who didn’t speak Turkish.

AS: How were you received in these villages as a young Kurd?

GA: My first assignment as a teacher was to the village of Altınakar in Diyarbakır. It was a village that belonged to an agha [1] . The school, the lodgings, the classrooms were dilapidated. Poverty. When we’d go to gather up the children, the women would throw stones at us during cotton harvesting period. We’d get upset, thinking the children would remain ignorant. Our mission was to enlighten the children following the Kemalist ideology—this is why I had picked the periphery of Diyarbakır. To serve my people. But the women threw stones at me. I was very upset. I was inspired by Kemalist ideology, but I also defined myself as a leftist. I always felt isolated from society as a female teacher; I always suffered. Whenever I went down to the city, they’d gossip that I was seen with men. I’d go to Diyarbakır Gazi Caddesi[2] in the historical Sur district. I’d usually take male students with me. I’d go to meet fellow revolutionaries, eat, and socialize.

AS: Did feeling alienated make you want to move abroad?

GA: When I was a young student in Urfa, in the boarding school for teachers, the midwife wouldn’t share her bathroom with us, the Kurdish teaching students. Think about it: the midwife is someone who has practical responsibilities. Every time a child was born, she’d receive so many gifts. Being a teacher was the exact opposite, a figure alienated from the community. This is what Turkish education meant in Kurdistan at the time, an extension of Turkish colonization. When the inspector came, he asked: when was Atatürk born? When was the Republic of Turkey founded?

AS: Teaching and education were disconnected from the socio-political, economic-political problems of those families.

GA: You take a child who is helping his/her father in the fields and tell them that they will learn the alphabet. You teach them, despite the poverty. You teach Turkish programs to the children of fathers who learned Turkish in the army while they were being beaten. I felt like an arm of the state. When we’d instruct the children to sing the national anthem in the village square on Fridays, the men would gather and stare at us. It felt like a strange play.

AS: Your mother immigrated to Germany as a worker after your father passed away.

GA: Yes, my father always helped his friends immigrate. He also wanted to go abroad, but he knew that he was very ill and wouldn’t make it. My mother was aware of the process; she took the exam three times before being selected. Do you know what this means? Empty the house in Elazığ, leave my younger sister with relatives in the village, travel to the big city of Ankara and take the exam. She failed the medical examination twice because of her kidneys. Germans were seeking healthy guest workers and my mom had kidney problems. She succeeded the third time in 1970.

AS: When did you decide to move to Germany?

GA: I didn’t think about it. My older sister and I took the university entrance exams in Elazığ. The fascists were the majority there back then. We took the exam without getting prepared. There were fascists sitting behind us, fascist male students taking the exam. I was very anxious; neither of us succeeded. It was like death. My sister went for the oral exam. They asked her: Are you Alevi? Are you Sunni? What newspaper does your father read? Of course my sister didn’t say that we are from Ovacık. It was very painful. Boarding school was already alienating. When we were thrown into real life, we were even more devastated. I’d ask myself what I was doing there, why I was there. I loved children; I’d share everything with them, even though I didn’t make much money. I soon realized how pointless it all was.

AS: You then came to Germany.

GA: Yes, first Aschaffenburg, later Frankfurt for school, and then Berlin.

AS: You even became part of a Jewish women’s group in Berlin: Schabbes Kreis (Schabbes Circle)[3].

GA: And of Evangelische Kirche's (Evangelical Church) Internationale Frauengruppe (International Women's Group). It was first established in Frankfurt. I still see my friend Maria [Roth], whom I met at that time. We met around 1978.

AS: So what did Frankfurt mean for the leftist Gülşen?

GA: The first thing I thought about when I saw the greenery was how I wished the sheep from our village were here. Back in Dersim, we would take the sheep and the lamb so far out into the mountains for grass.

AS: Could you talk more about the women’s group?

GA: In our international group, we had women from Iran, Turkey and Germany. When I went to Berlin, I met Dagmar Schultz in a similar women’s group.

AS: You were working with feminist women? How did you become involved in Schabbes Kreis?

GA: When I first began my studies at the university in Frankfurt, I was focusing on the Holocaust, as someone who comes from a Kurdish family who experienced genocide [The Dersim Massacre[4] ]. You could feel the impact of the Frankfurt School. Nothing is coincidental. When I first arrived, I was interested in Jewish literature and Jewish women poets: Mascha Kaléko, Nelly Sachs, Rosa Ausländer, etc.

AS: In other words, the Holocaust enabled you to think about structural violence and to self-organize politically in a different way. It led you to Schabbes Kreis. What made this group special for you?

GA: When I first joined the group, I was pregnant. My son is also a Schabbes child. He was born on a Friday night. [Smiles. Continues in German]. I found the way they dealt theoretically with anti-Semitism, racism and homophobia, spot on. I’d go to their readings as a political subject. For example, I went to a reading of Farbe Bekennen [5]. I first became aware of this book thanks to Schabbes Kreis.

AS: Could you talk about the book?

GA: Farbe Bekennen was May Ayim (given name May Opitz)’s thesis. It is the first comprehensive work that deals with Germany’s colonial past, which Germany has tried to ignore. It addresses the Afro-German women whose self-definition was hindered because of European colonialism. Here, Audre Lorde is very important. With her initiative, the Afro-German women’s groups started to meet, (ADEFRA: Afro-Deutsche Frauen). Audre participated in that reading actually. This is why that group was very important for me. I was able to interpret the racist experiences I had lived in Germany within a theoretical framework.

AS: There were important feminist women around you, especially the PoC women activists of the time.

GA: The white women’s movement never accepted foreign women. This is why the solidarity among women in the 80s was very special to us. Could I talk about this in Turkish? I can’t express myself well enough in German on this subject. For example, we had a Jewish friend Susanne (Stern), from Vienna. She studied our genealogies. This environment reinforced our self-awareness by affirming our presence and histories. At the time, there were other women’s groups against racism, but for me, being in a political group that worked both on anti-Semitism and racism was very important. The white women’s movement always saw migrant women as victims, as passive subjects. You also see the colonialist perspective here. A white feminist, colonialist perspective. We were against that. There is an anecdote I’ll never forget. A student group came to Urfa from Istanbul; I was too embarrassed to even open the door, too embarrassed to talk. To be embarrassed, to feel inferior: I have thought a lot about these feelings. During the time of the 1971 coup d’état, an 18-year-old Turkish soldier pulled the moustache of a Kurdish parent at my school because he didn’t have an ID on him. There are times when you can’t do anything and nobody around you says anything. You are always pushed to the side; you have been repressed. But through such women’s groups, you learn to see things differently. We formed a theoretical framework for our experience through each other’s experiences.

AS: Why do you think this movement flourished in the 1980s Berlin?

GA: The wall. The wall shielded us from the outside. It functioned as a political niche. I’m not able to do a more in-depth political analysis… For example, people who did not want to serve in the military were in West Berlin. But I thought Frankfurt was more special. The university publications and discussions were deeper.

AS: Do you have memories of Audre Lorde in Berlin?

GA: Of course! Whenever she came here, I would stop by to visit Dagmar’s (Schultz) more frequently. Audre used to come often for her treatment. When she passed away, Dagmar gifted a few of her belongings to me. There was a quality in her that I really liked. Because of her illness, one of her breasts had been removed. We were outside one day, she was wearing a t-shirt made of thin material; it was obvious that one of her breasts was missing. Her courage was really inspiring to me. One day, I was in a cafe with friends and I saw her in the streets carrying shopping bags. I told my son, who was 7 or 8 at the time, to go and help her. He ran over, but Audre didn’t give him her bags. I was annoyed. I saw her quite often, also when her partner Gloria (Joseph) came here.

AS: Why were you annoyed?

GA: I was trying to teach the kid how to help others. She should have thanked him so that he felt proud and learned something. Well, at the end, he did help her.

AS: You have two sons. What are your thoughts on marriage?

GA: Since I was a child, I always thought that marriage had a theatrical side to it. It was different in our village. We were matriarchal; we had a different theatricality. Feminism doesn’t descend from the heavens! From a young age, I understood that women and men were equal; I come from a matriarchal society. Alevi, Kurdish, from Dersim. We also have a half-migrant family structure. We would go up to the highlands during the summer. My grandfather and my uncle would milk the sheep, make the cheese, the yoghurt: all tasks traditionally assigned to women. When my grandfather came back from the fields, I’d bring him water, but he’d wash his socks. When his socks had holes, he’d fix them. This is the kind of man I observed. I never saw myself in a wedding gown. So I never got married and I would never get married.

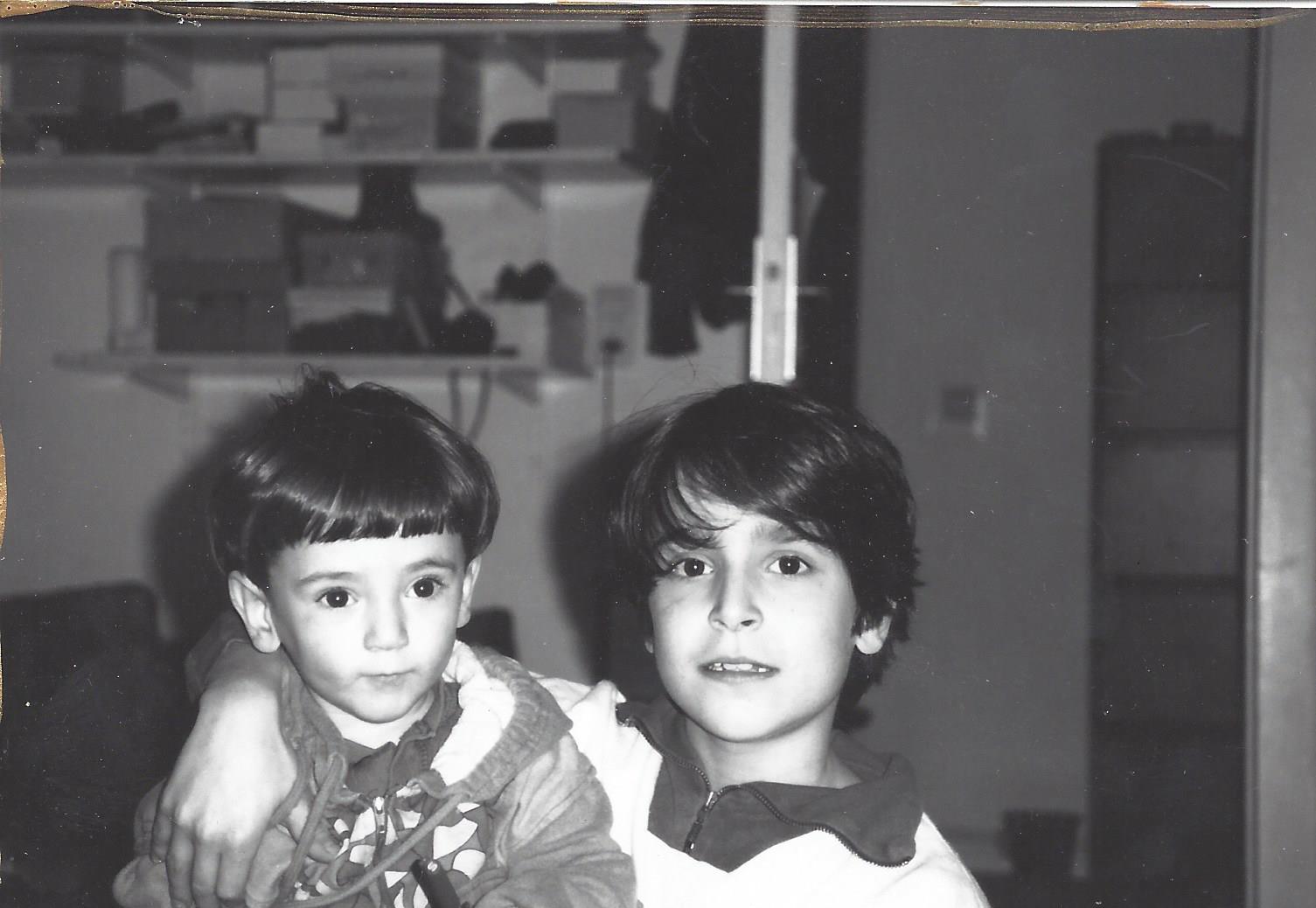

AS: Your kids grew up with your female friends. Could we say that they grew up socially amongst women?

GA: I tried to raise my children to be warm towards people. I was almost harsh with them. My female neighbors would sometimes warn me not to scold them. They became warmhearted people in spite of me. My feminist friends loved how they would jump up and hug them every time they saw them. When my younger sister came out as a lesbian, my older son would go to school and flaunt it. I never told them to act a certain way, but they developed a certain way being in that atmosphere.

AS: We always meet at the Sankt Mättheus cemetery in Schöneberg to visit your mother’s grave. What is the importance of this place for you?

GA: It is one of the most interesting cemeteries in Berlin. When my mother was alive, we’d go there for visits, and I’d read there. Then a cafe opened. A cafe creates a whole different atmosphere. A lot of people are buried there. May (Ayim) is there, close to my mother’s grave. As you know, a lot of gay people who died of AIDS, beloved rock-stars, the Grimm brothers, resistance activists are buried there… It is a place where not only Christians, but also Muslims and Jews are buried. It is a nice feeling to go and water those graves, to plant things…

AS: Is there a poem by May Ayim[6] that you like?

GA: Grenzenlos und unverschämt[7].

AS: How would you describe May?

GA: Righteous. She was quiet and respectful. She didn’t place herself in the foreground. Sometimes, I think that if May had been a classmate, teachers would tell other students to be like her. She was modest. I once heard that she was applying for a job, and the moment she learned that a friend was applying, she withdrew her application. This gesture made a huge impact on me. I also know of the time when she was ill. I was very upset after her suicide. I cried a lot. She was a very important woman for us. She still is. You know there was a memorial for her the other day, and you yourself heard about her from all those people who came to the memorial.

AS: Today, death isn’t political…

GA: We talk as if there is no death in capitalist societies. As if we only live by the day, as if this world exists day by day. These norms alienate me. I feel lucky to live close to a cemetery. Everything is meaningless. I’m about to turn 59. I’m a melancholic person. You’re here today, you’re not here tomorrow.

AS: The institute that you are directing in Schöneberg right now, (Esperanto e.V. : Huzur Buluşma Merkezi) is a club for the elderly. The people who live here make use of your services and the recreational activities you organize. Do you borrow experiences from your past work with women to run your organization?

GA: After a trip, for example, some women complained about others bringing their husbands along. We then offered activities specifically for women, for example, for women coming from Turkey. Being able to share freely only happens when there are no men around. We sometimes talk about husbands and won't stop laughing. There are friends here who have stories of migration from thirty different countries.

AS: What kind of activities do you organize?

GA: For example, I invited Karin Karakaşlı, who is an Armenian poet from Turkey; Fethiye Çetin, who was Hrant Dink’s lawyer. I don’t have resources, but I try to organize things that give people hope. Let me talk about the neighborhood. We are where Frobenstraße intersects Bülowstraße. This is a neighborhood where sex work is visible on the street. It is a place where trans and cis-gendered sex workers are present. When we were moving here, people were prejudiced. I vehemently protested. Schöneberg, for example, is a neighborhood that is predominantly male gay. I wanted to work alongside these groups as well. Just as I’m against the latent racism against our community, I will also not tolerate the prejudices in our own circles. This is where we showed your film, Off-White Tulips, for example. We need to hear different voices. We need to resist the racism and homophobia in our own worlds. I think about these things as I prepare the program.

AS: In 2014, I designed a pop-up choir performance at the Neue Nationalgalerie, referring to an art action by Ulay in 1978. Shall we talk about this a little bit? Ulay designed this performance as an illegal action. He stole a painting by the German painter Carl Spitzweg (Der Arme Poet) and hung it in the house of a Turkish migrant family. You worked as a producer in my restaging of Ulay’s action, and you relayed my invitation to people who’d want to participate in the Turkish traditional music choir I was trying to form. For the first time, first-generation Turkish migrants entered through the doors of Neue Nationalgalerie, which is an institution that exhibits ‘high art’, and they formed a choir in the middle of this space. You were also in that choir. What was this experience like for you?

GA: You know, I was very nervous. I have a perfectionist side. I was really scared that people who attended the rehearsals wouldn’t show up for the performance. I wouldn’t say that I learned what I learned about art from you, but I did learn how to go deeper thanks to you.

AS: Women were in front of an audience for the first time. Our choir was like a short-lived, autonomous system; it appeared quickly, created a beautiful resonance, and then disappeared. We filled the space with our voices and then left. How did you experience this process?

GA: I used to go to exhibitions at the Neue Nationalgalerie. But for us to go there and sing the song Çile Bülbülüm with an orchestra was a very different experience from anything I had ever seen there. It was surreal. As someone who has Çile [suffering], singing a song I loved at the Neue Nationalgalerie was like singing it on Mars. It was a beautiful day.

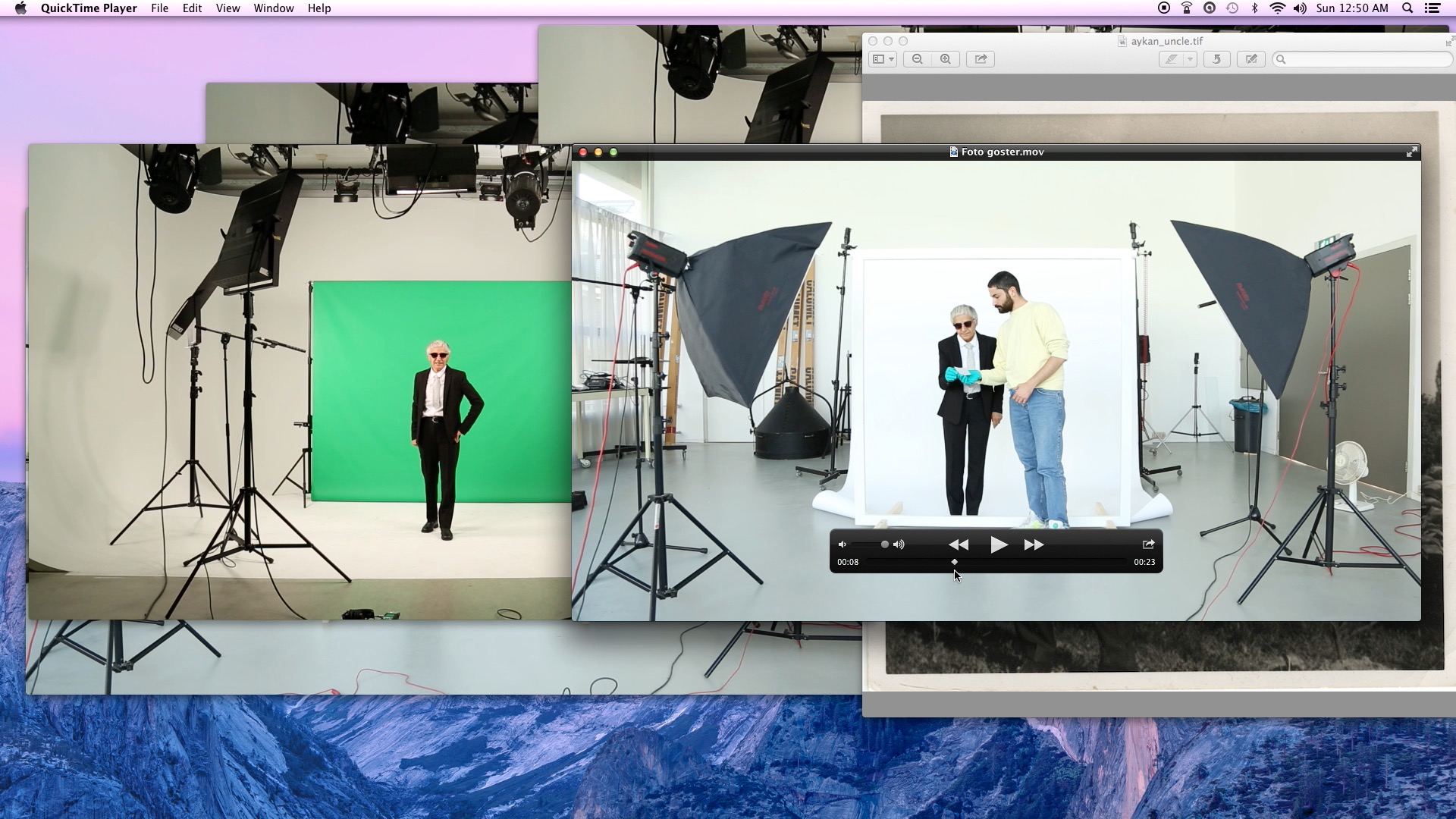

AS: What about last year? When I told you that I wanted to make a work about my uncle who came to Germany as a migrant and who killed himself here. When I told you that I wanted you to be my uncle in this film (Untitled: Gülşen and Hüseyin), what did you think?

GA: Actually, you brought me a huge present that day, but you were also very sad. I cooked, you didn’t eat anything, you kept crying. You asked me if I wanted to be your uncle, crying. Of course, if you ask, I’ll help you. I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to do it. But mutual trust is very important; you are the apple of my eye. I accepted because I trust you.

AS: When this work was shown in Oberhausen, a moderator told me that they were disturbed by the fact that my uncle was played by a woman. What would your response be to this comment?

GA: I’ve been preoccupied with gender roles since I was a child. I’ve had trouble abiding by gender norms since puberty. I don’t come from the kind of female bonding that is socially accepted. Since my father passed away at an early age, I was responsible for family business. So when you asked me whether I’d be your uncle, I didn’t find that strange at all.

AS: I didn’t either. I thought about it as soon as I had the idea for my video. I thought that someone who came from a female experience could also do it. Manhood is something one learns. Another question people ask me is: Gülsen is your friend, why is she in the role of a family member?

GA: Why would I not play your uncle? I could have been your aunt, there is an obvious age difference between us, but I could also be your uncle. I’m the daughter of a widower; I have a harsh expression. There is a saying in Turkish: “You need to be so strong that even a male fly who lands on you dies” [pointing at her face]. You need to walk like the military police.

AS: You could also criticize me, since I come from a male experience. What if you were to criticize my art?

GA: As a friend, going to art exhibitions with you is an honor. I say this with all seriousness. I’m not pampering you as a friend. What is it to look? To look at art? I’m trying to learn from you how to look more deeply. I like that. But I’m curious; why don’t you make popular art? For example, if you were to make a film about matriarchal society, is there anybody out there who’d tell the story better than you?

AS: You’re saying that I should do something more mainstream?

GA: Yes. What you are doing is too profound, very layered. Sometimes, even I don’t understand it, son. But still, I liked my outfit in the last film. Even though my movements are stiff, I still think that you made a good decision choosing me as your uncle Hüseyin.

AS: What were your impressions about working together? Do you have any criticisms? Or suggestions?

GA: People wear blinders. If you put the label “sweet” on hot pickles, people will think they’re eating dessert. Don’t mind what others say. When I look at Gülşen, who is dressed as your uncle, I see someone concerned with death. This is not an idea that is distant to me; that of suicide. But I don’t have the guts. I love life. Questions emerge from your questions, and one starts to look at things in a different way.

AS: Are there women’s movements that excite you today?

GA: The other day, I watched a documentary on Kurdish guerilla women in Kandil on Arte. I felt very emotional. Twenty years ago, I watched a documentary about a woman activist who formed a militia against rapists and molesters in India at the Berlinale. That was also very moving!

AS: So you care about women fighting for their rights to self-govern and self-defend? In other words, Rojava! What is Rojava for you?

GA: I’m always excited by the pursuit of a feminist politics, for women to be in certain positions. I’m most excited by women’s excitement.

AS: What is our favorite meeting place?

GA: Where I go to smoke cigarettes: Neues Ufer [laughter]. I’m very comfortable there as a woman. It is a place frequented by gay men, where I form new friendships through humor.

AS: You know that’s also where Iggy Pop and David Bowie first met? We should say that so that more customers come! [Laughter]

GA: Tourist groups already come here. I’m comfortable here. I need peace of mind.

- “Agha" is a title given to tribal chieftains or to village heads.

- Diyarbakır (Kurdish: Amed) is the unofficial capital of Turkish Kurdistan. As such, it has been a focal point of conflict between the Turkish government and Kurdish insurgent groups. In the aftermath of the general elections of June 2015, between November 8, 2015 and May 15, 2016, large parts of the historical Sur District were destroyed by the Turkish military in the fighting with the PKK (The Kurdistan Workers' Party or PKK. In Kurdish: Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê). Diyarbakır Gazi Caddesi is the central avenue that divides this historically important cultural, urban center and has been the main site to recent clashes.

- Schabbes Kreis (Friday Group) is a feminist, women’s group that was politically active in Berlin in the 1980s, focusing on racism and anti-Semitism.

- The Dersim Massacre was a massacre of Kurds (Alevi Kurmanj and Zaza) by the Turkish government in the Dersim region of eastern Turkey, which includes parts of Tunceli Province, Elazığ Province, and Bingöl Province. The massacre occurred after a rebellion led by Seyid Riza against the Turkification policies of the Turkish government. As a result of the Turkish military campaign against the rebellion, thousands of Alevi Zazas died and many others were internally displaced.

- Farbe bekennen (Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out) is edited by May Ayim, Katharina Oguntoye, and Dagmar Schultz and published in 1986. It is the first book published by Afro-Germans and the first written use of the term Afro-German. This book is a compilation of texts, testimonies and secondary sources. The collection brings to life the stories of Black German women living amid racism, sexism and other institutional constraints in Germany.

- May Ayim (3 May 1960 in Hamburg – 9 August 1996 in Berlin) is the pen name of May Opitz (born Sylvia Andler), an Afro-German poet, educator, and activist. The child of a German mother and Ghanaian medical student, she was adopted by a white German family while still young. After reconnecting with her father and his family in Ghana, in 1992 she took his surname as her pen name. Opitz wrote a thesis at the University of Regensburg, Afro-Deutsche: Ihre Kultur- und Sozialgeschichte aus dem Hintergrund gesellschaftlicher Veränderungen published as the book Farbe Bekennen (1986). It was translated and published in English as Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out (1986). It included accounts by many women of Afro-German descent. Ayim worked as an activist to unite Afro-Germans and combat racism in German society. She co-founded Initiative Schwarze Deutsche (Initiative of Black People in Germany) in the late 1980s.

- Borderless and Brazen is a poem by May Ayim.